Found these three cuddling candies on a huge rock after finishing a piece of writing. I am so grateful to the person who placed them here. So generous, so sweet.

1/3/25

I’ve just removed my WhatsApp™ account. Today I provided the last bits of service work for Meta™ – which has rarely served me and my loved ones. It never was an equal working relationship, anyway. Find me on Signal instead.

15/2/25

22/12/24

23/6/24

er is tijd nodig om te omarmen wat onbruikbaar blijft

18/5/24

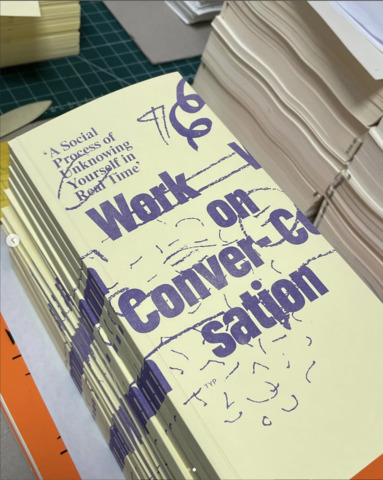

The German radio broadcaster Deutschlandfunk Kultur recorded an episode dedicated to Schüchternheid, which I don’t think is really translatable to English. They discuss the power and protection that coyness offers to the imagination of the writer, or any human being, really. But now that I come to think of it: decoy comes from the Dutch de kooi, which stands for the cage. So coyness in a sense points to a self-chosen place of reflection and in my opinion, restitution, since especially seclusion often occurs in relation to something else. Even if it is untracebly separated from it. I have to think of the astrological water signs who almost always need to give something back to the world, also if this act remains entirely unnoticed. They are concentrated enough not to bother with its reception, knowing that it will find its place.

Here is the link to the Sendung, which also includes a full-length manuscript.

3/5/24

ode aan rolduc #2

2/5/24

ode aan rolduc #1

ik vond hem op het stoepje

van een langvermeden klooster

de majestueuze tuin was dicht

het kraakpand open

we schoven inelkaars boeken

terwijl het bovengelegen koppel

italiaanse namen vermorzelde

door het verbruik

van televisie

13/3/24

How to remain an unusable suspect?

26/2/24

Exploring the literary heritage from Balıkesir, where my grandfather is buried, I have been reading Sabahattin Ali’s Kürk Mantolu Madonna from 1943. It tells the story of a twenty-something who is sent to Berlin to work in a soap factory in the 1920s. In his free time, he goes to museums and galleries that have started to re-open after the war. One one day, he discovers a self-portrait by a young woman, a painter. He is entranced by the piece and returns several times. Aside from the story that unfolds later on, I am very moved by the sustaining energy this piece exerts on him. Why have I felt the need to endlessly pursue new artworks, literatures and positions? Or Horizon(s)™ as Meta has branded it for its VR headset.

As an alternative I have felt more drawn to engage with Ali’s attitude, in which one trusts one’s personal history of artistic exposure to be more than enough. When I reflect about some of the artworks that have marked me up to this day, I feel that I already have seen so much, as if I will need the next thirty years to process and distill all these impressions into my own (un)making. Perhaps it is helpful to think and work in tune with Saturn’s cycle? Another person who I want to rely on, is Tait, who had also decided to trust on the formative aesthetic experiences that she was exposed to in her younger years. She did not try to surpass or move on from the neorealist filmmakers, but intimately admitted their resonances. And yet her practice remained timeless, which must have come from her need for integrity, and that this in itself eludes the grasp of trendy orientations. Is this about how to dance with the Zeitgeist in an ephemeral and opaque manner, instead of doing so programmatically?

15/2/24

22/1/24

In Blanchot’s book Friendship (1971), I discover a chapter called ‘’The Great Reducers’’ in which he criticises the invention of the mass paperback. I am not sure about the derogatory title, since I am a fan of reduction, which I believe he was too. So what did he mean? And who? As the chapter progresses, it becomes clearer that he talks about the market and how the paperback was a way to interfere in the communities of writers, how the endless duplication of a book made the published authors, with Sartre as his prime example, become ‘’bigger than life’’ and spill out of their given proportions. I believe that this text is relayable to our current time, and our enslavement to social media has replaced the wider availability of more tested outlets of publishing, testing and pushing us even more in return.

Heightened visibility and access came with the introduction of the paperback, before the internet pushed both a mile further, and making us habitualise the process of turning intrinsically meaningful books into flaneurable fashion items. I agree when he argues: ‘’...at the same time, one offers the old classics, the writers of Mao Tse-tung, a volume from the Presse de Coeur, the Gospels, the works of the ‘’New Novel’’; one goes so far as to publish (and this is the subtlest subtlety) an innocent excerpt from Sade, but quite obviously it is not in order for it to be read but rather to proclaim it: See, we publish everything, we have published the unpublishable Sade. However, there are economic imperatives with an altogether different end that correspond to this claim of totality.’’ (p. 69)

What he was interested in, is how to keep returning and reducing to the most creative conditions in which the work is not lost or untransmitted due to economic or cultural stakeholders. He ends with a saying by René Char, and that I will largely quote: ‘’The ground upon which [culture] raises itself and to which it refers is still culture; its beyond is itself, the ideal of unification and identification with which it merges. [...] Culture is right to affirm it: it is the labor of truth, it is the generosity of a gift that is necessarily felicitious. And the work of art is but the sign of the ungrateful and unseemly error for as long as it escapes this circle (which is always expanding and closing itself) (social media nowadays? — Kaya). Will this doom the writer — the man who puts off speaking — to the impractical lot of having no other choice but to fail by succeeding or to fail against success itself? I will first ask the question of René Char. And here is his response: ‘’To create: to exclude oneself.’’ (p. 71)

This essay is my prompt to finally start reading Régis Debray’s Transmitting Culture (1997). which Emmalea recommended so warmly in Cosmic Edges. Do subscribe to her fabulous newsletter!

13/1/24

Iech bin gistere de ganse daag in Luik gewees, en ‘t heit miech verbaas wie ‘t kin tot iech es Mestreechteneer neet ieder miene sjatpliechtegheid aon dee stad erkent höb. En allewel iech pas sinds de zomer vaan ‘t veurig jaor Frans aon ‘t liere bin, kos iech noe al allemaol nuie dinger oontdèkke en verstaon. Bookhandels, galleriekes, gewoene conversaties op straot. Miene levelingsgalerie in de streek ligk dao, sjus wie Livre aux Trésors; deze plek aosemt leefde veur beuk. Missjiens is ‘t zoe dat sjatpliechtig zien aon de wortele en vertakkingen es ‘ne luxe zou motte weure besjouwt, en neet es ‘n pliech. Zeker es iech naodink euver mien vrun oet ‘t Midde-Ooste veur wee deze vörm vaan sjatplichtigheid neet mie veur te stèlle valt.

8/1/24

Listening to the December Rhapsody album that tori kudo released a few hours ago. For me it is evident that he is an amateur of the most wonderful kind, since he practices and lives his love for music more than any other musician I have heard, and yet he lacks complete traditional ‘’skill.’’ He does not possess anything as a classical author and master who rules his domain. Not his music, nor the intricacies of his practice. However, I think this ‘’yet’’ is false and misplaced, since the time he used to sustain his amateur spirit completely altered the roots of his development. Traditional education and disciplinarisation would have undermined this flow, and only accumulated a different and more recongisable ‘’continuity.’’

7/1/24

26/1/23

#2

as above, so above*

the diary

for me

is the most unprivate form

since its shape, its surface its denomination

already

externalises, eradicates

its inner perplexions

the many publicly-discussed associations

shatter its subsumption of the intimate

this my mother taught me

as an early certitude:

she gave me a tiny diary, with an even smaller lock, covered by a gloss of fake gold

and i filled it with myself

until i discovered that she had broken the lock, the size of my pink,

my minimus,

flowering into the lawfulness of de minimis…

a legal doctrine concerning things that are so minor

as to be negligible, trivial or trifling

this provided me with the earliest hint, suggestion and flirt

that unrecognisable forms, shapes and viscitudes

will do what she always refused

to hold a breath for me

and that i will contract

back into my household

as i slik** it back

into the vulgarity of this inexpansible corridor

that is my vernacular: an unsailable hush and gasp

a vernacular that i cannot write yet

the concurrent need to testify

to pull

all the wor/l/ds to the surface

to leave nothing vacant and underneath

these definitional marks

shock me with their ruthless clarity

and it is in the extended sequencing of his grave,

via the outlines that also determine my own corpus

that the publication of his chiselled stone has become fact

the english you are reading, is becoming ornament

every word an etalage

akin to a grave that has been dragged out

into the shyless open, fully discernible in its blatant explicability

where only moon says ‘’moon’’

and sun listens to ‘’sun’’

the diary

for me

is the most unprivate form

since its shape, its surface its denomination

already

externalises, eradicates

its inner perplexions

the many publicly-discussed associations

shatter its subsumption of the intimate

this my mother taught me

as an early certitude:

she gave me a tiny diary, with an even smaller lock, covered by a gloss of fake gold

and i filled it with myself

until i discovered that she had broken the lock, the size of my pink,

my minimus,

flowering into the lawfulness of de minimis…

a legal doctrine concerning things that are so minor

as to be negligible, trivial or trifling

this provided me with the earliest hint, suggestion and flirt

that unrecognisable forms, shapes and viscitudes

will do what she always refused

to hold a breath for me

and that i will contract

back into my household

as i slik** it back

into the vulgarity of this inexpansible corridor

that is my vernacular: an unsailable hush and gasp

a vernacular that i cannot write yet

the concurrent need to testify

to pull

all the wor/l/ds to the surface

to leave nothing vacant and underneath

these definitional marks

shock me with their ruthless clarity

and it is in the extended sequencing of his grave,

via the outlines that also determine my own corpus

that the publication of his chiselled stone has become fact

the english you are reading, is becoming ornament

every word an etalage

akin to a grave that has been dragged out

into the shyless open, fully discernible in its blatant explicability

where only moon says ‘’moon’’

and sun listens to ‘’sun’’

*this poem is a sequel to silent, minor, grave, and will be presented as part of a collage folio in a show in Belgrade next month, in which I will also show the film from which silent, minor, grave emerged, together with a new essay and several small drawings

**meaning: ‘’to swallow’’ in Dutch, my mother tongue

addendum (20/03/2024): ‘’It is easy to mistake arbitrariness for something no more significant than a scholastic paraphrase of Shakespeare’s “What’s in a name? That which we call a rose / By any other name would smell as sweet.” One need hardly be a linguist to realize that the sound shape of the word rose has nothing too with the object it “names.” The situation recalls what Saussure once said about language in general: it seems obvious to everyone what “language” is, yet it is precisely the deceptive clarity of the quotidian perception that plunges the matter into a fatal confusion.’’ (From: Beyond Pure Reason: Ferdinand de Saussure’s Philosophy of Language and Its Early Romantic Antecedents, p. 71, Boris Gasparov, 2012)

addendum (20/03/2024): ‘’It is easy to mistake arbitrariness for something no more significant than a scholastic paraphrase of Shakespeare’s “What’s in a name? That which we call a rose / By any other name would smell as sweet.” One need hardly be a linguist to realize that the sound shape of the word rose has nothing too with the object it “names.” The situation recalls what Saussure once said about language in general: it seems obvious to everyone what “language” is, yet it is precisely the deceptive clarity of the quotidian perception that plunges the matter into a fatal confusion.’’ (From: Beyond Pure Reason: Ferdinand de Saussure’s Philosophy of Language and Its Early Romantic Antecedents, p. 71, Boris Gasparov, 2012)

26/1/23

#1

I think it makes sense to elucidate my turn towards this very page, away from all other attention-diluting platforms. Some years ago, Masha Tupitsyn, a writer who I have always read with great pleasure, removed and decreated herself towards her own webpage: in a sense to regress to a lost phase of the Internet. She is no longer present anywhere else but through her books and teachings. This form of concentration always lingered with me, and yet I was too afraid to take a similar step. Due to my recent engagements at Les Orangeries de Bierbais in Belgium, but also the affirmation of myself as an amateur, I have realised the room to decreate – to speak with Weil, Carson and Robertson. To commit to an attention that is pointed towards distillation, from which contact and correspondence will eventually result. This is a faith that has to be practiced, one less based on careerism and the endless expansion of networks, but more on intrinsically shared pursuits and desires.

25/1/23

Only recently I became aware of the following confusion, which I believe is widespread among anyone who engages with both local and global cultural scenes: that we need social media in order to socialise our artistic practices, a dictum that every active user has to subscribe to and believe in, otherwise he or she cannot properly participate.

I think that more and more we should assume our existing practices as socialising media in themselves, for which we do not need to depend on a platformising agent that will disseminate our work, no matter how opaque our themes. Meta in particular has different interests in mind, and to ‘’share’’ our work with love is not one of them.

To initiate this private changement de décor, away from an overtly visible stage, I have gifted myself Hannah Arendt’s final dissertation on love in the work of Augustinus. How has the labour of love moved from something that reflects our own interior castles to a kind of love that is more about the like, an accumulative affect that is concerned with circulating external projections?

This page from Ariana Reines’ Mercury made me more wary of the Mercurial energy that is quite expressive in my birth chart, and I wonder: how does Mercury function once it is subjected to affective refrain? What will it do once it is unable to express itself freely and abundantly? On Friday I will attend a workshop and reading by Ariana in Amsterdam, to witness her work in the flesh for the first time.

16/1/23

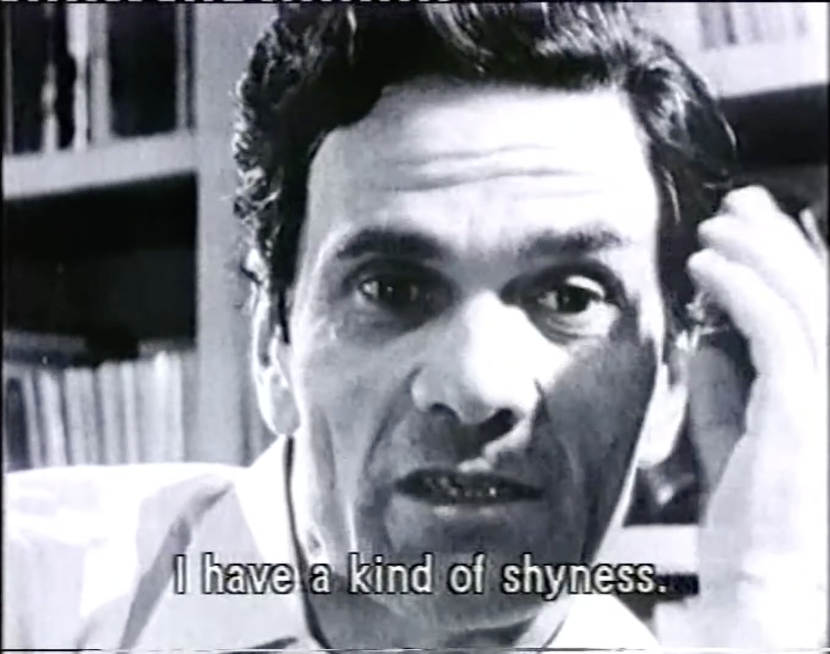

Since my last daily, I have tried to let Pasolini’s shyness envelop my orientations. In tandem with starting a horticultural apprenticeship, I have moved to Houthem, the village of Saint Gerlach; a 12th century hermit who lived in an hollow oak tree. The scraps, pepeerkes and other traces that you will find in this space, will hopefully have the capacity to chase away the transparent, to let a multifold of transparencies feel its own violence, and to invite the maddening slowness of the opaque. Iech hoop vaan harte tot geer mien ontowgaankeleheid veur leef nump, sjus wie de buste heioonder. Daank uuch wel.

De reliekbuste van de H. Gerlachus, zilver, hoogte 46 cm, door Fredericus Wery uit Maastricht vervaardigd in 1704-1706. Bijbehorend houten voetstuk. Opname 1999.

4/3/22

♓︎

It’s Pasolini’s 100th Birthday tomorrow, and we are also in Pisces season, which feels like the perfect moment to think about his shyness, my own, and everyone else’s —and especially how they interrelate in a world where transparency gets ‘’awarded’’ on an minute-to-minute basis. And how not hiding our shynesses is a method to share that there is always more than meets the eye. That’s also the reason why I want to keep this part of my web-site a little bit hidden, for those who are willing to scroll down, expecting that there is nothing else, nothing much.

6/3/22

A Casa, a Verdadeira e a Seguinte, Ainda Está por Fazer (2019) by Sílvia das Fadas

What a surprise: Sílvia das Fadas visited and filmed Robert Garcet’s castle, which is located very near to Maastricht in Eben-Ezer. Initially I wanted to write a post about this film on Instagram, but for a film that is not interested in visibility and measurable feedback, this part of my place on the internet seems to be more suitable.

In a phase when I am trying to cultivate what the British psychoanalyst W.R. Bion called negative capability, I see das Fadas as a possible example of someone who wants to retain her freedom, with the courage to take deep plunges into uncertainty, away from the fixed nature of established institutions, even though she stays very much aligned with them. This seeming conflict leads her to mystics like Garcet, who surely had a grasp on negativity, and who could bear to live ‘’outside’’ and in an own space in which his work could be made. When I consider what it means to sustain my practice after graduating from GSA, I cannot help but think of the need to have just-enough private space for my thinking and making. Where I can have my studio, but also feel a different impetus than an oppositional one. To trust that my camera and my pen can ‘’contain’’ that negativity in a way that leads to the meadow instead of the graveyard? And is a local art scene as relational as people tell themselves? Does it not mask itself as such due to the opportunistic nature of its underdog status? I don’t know: I think I am partly right and partly wrong, but my deep affinity for people like Margaret Tait, whom’s integrity touches me ever more deeply than the juggling mores of a networking artist, speaks softer and quieter, and should that not be the only impetus for attraction and attention?

13/3/22

Yesterday, I finally visited the art exhibition on gardening at the Centraal Museum in Utrecht, before going on the ferry back to Scotland. It helped me to remember the key role that harmony has always fulfilled within horticulture, and the effects it might have on my artistic practice when I will become a horticulturalist myself.

Personally, harmony as a connective tissue has somehow slipped off my map during the last few months. What caused this? Perhaps it is an instinctive resistance to harmony as a mechanism for smoothing over difficulties of any kind, which happens a lot in my home region where I have been spending this period. This varies from how I have learned to perceive and seek out harmony in Glasgow, where its function and need is something that people are structurally deprived of. Some of the most wild and beautiful gardens have shown to be capable of creating room for many different plants and weeds to live together. In that sense the exhibition made me think of how harmony for some is the most radical thing, perhaps to those who are least used to it, whereas for others it is a reason to remain conventional and overly self-preserving. However, the line between both can be blurry, and difficult to trace back, so it was refreshing to see a show that did not avoid neither side of this question. A gut feeling says that this is not unrelated to most avant-garde practices in art history, in which separation and not co-habitation or integration was often effectuated. Some, and therefore the most exciting exceptions, did in fact accomplish a very delicate balance in this. Gregory Markopoulos and Robert Beavers, or Nathaniel Dorsky, have always enthused me in this regard, as they all showed how old structures of feeling can and should be re-orded in a way that stays with their respective troubles, while also subverting the form taken.

Shousha, Tunisia, july by Henk Wildschut

26/3/22

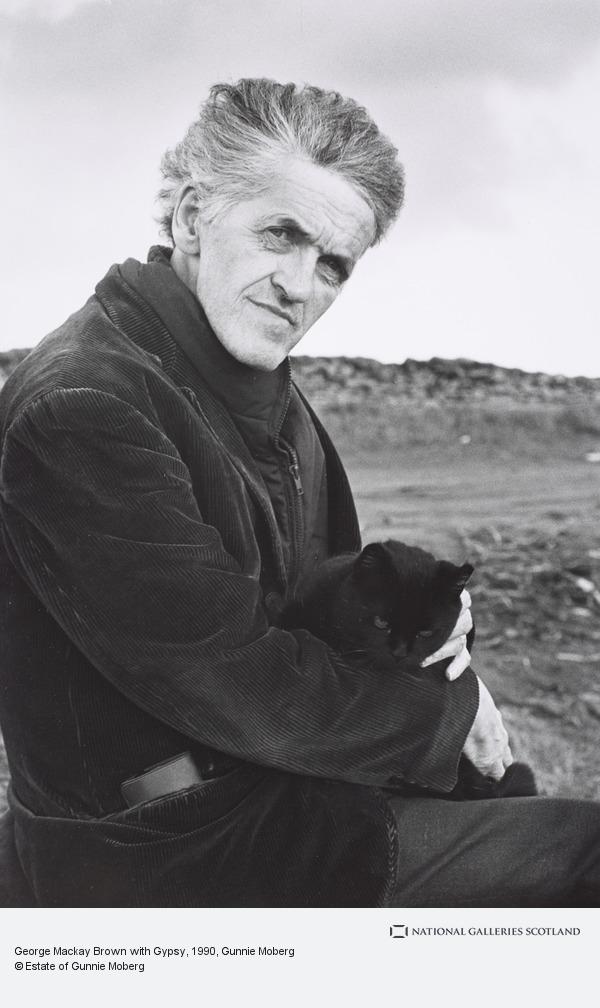

Today, on this very sunny Saturday, I looked for books by George Mackay Brown at the Caledonia Bookshop, and they of course had lots of him in stock. Letters from Hamnavoe is his bundling of pieces he would write regularly for The Orcadian, and the modest length of them made me think of what you are reading now. The themes he addresses in it, everyday ones and full of receptivity to mundane motion, returned to me a sense of Orkney that I got when I was there in December. This is basically just a reminder that I will have to go there now and then.

1/4/22

I sat next to an older, quiet woman during my travels the other day, and after working on a long poem for a good while, she asked me if I was writing poetry, a question I directly returned to her and, timidly, she confirmed. We did not say more. How rare and special is it to have these encounters of mutual understanding, and a confirmation that whatever you do is already all you have to offer.